Microbes, banana beer and their impact on immunity

Bacteria, viruses and other microbial life forms inhabited the Earth much longer than ourselves and will likely stay at the party much longer. Genetic diversity and adaptation to the environment is the key to survival. Every so often, as in the past two years, this lesson is re-learned the hard way.

Some of these bugs live happily inside human guts (skin, mouth,..) and represent an important organ, referred to as the microbiome. They can perform diverse digestive functions, like break down your granola bars and enjoy breast milk! Importantly, they also play a part in educating our immune system from the early age.

While our genetics are imprinted and mostly fixed from birth, microbiome is much more sensitive to enviromental changes. Rapid urbanization, especially in low-to-middle income countries, has led to notable changes in microbial diversity, as well as a rise in non-communicable diseases. African populations in particular encompass a diversity of lifestyles and opportunities to detect ecological niches, as well as a pervasiveness of autoimmune diseases and epidemics.

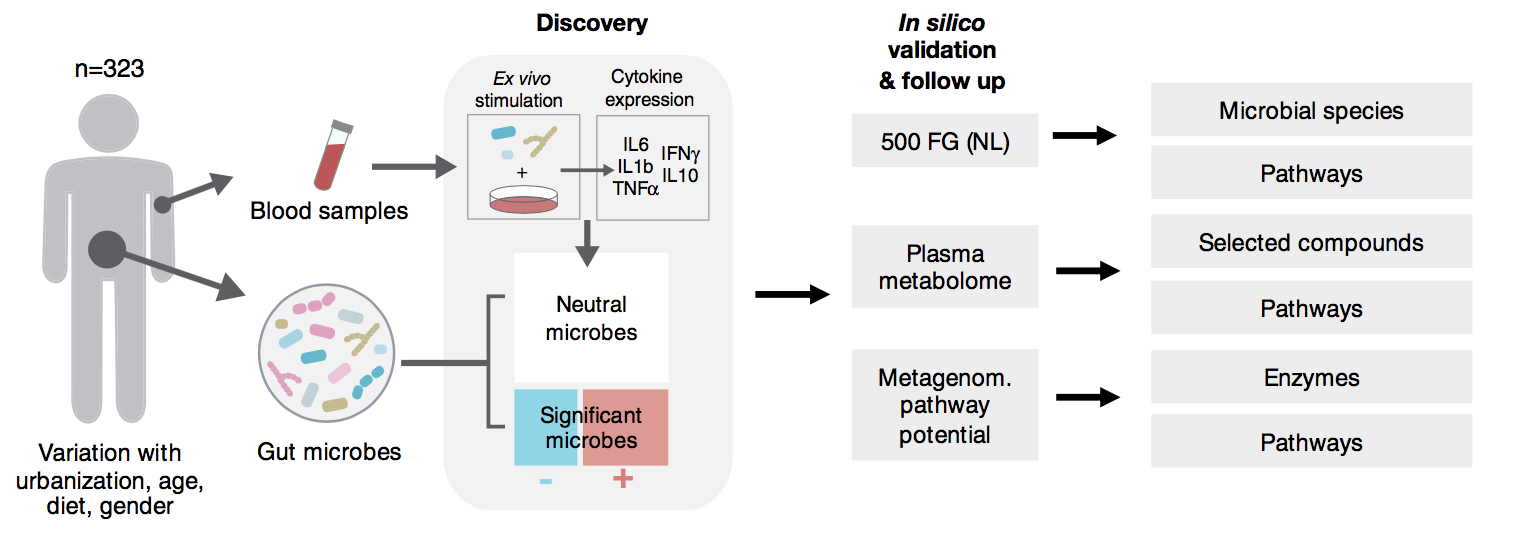

In our latest study, we examine gut microbiome of more than 300 Tanzanian individuals from rural and urban enviroments. We highlight how urbanization brings microbiomes closer to that of developed, European populations. Rural participants, which often depend on traditional diet and habits, like brewing banana beer or having limited access to drinking water. They show snapshots of interesting bacterial profiles likely resembling our distant past.

All of this has important consequences for human metabolism and immune functions; in particular, we find that blood cells of urban participants are more inclined towards inflammatory responses when presented to common stimuli like E. coli, tuberculosis, or pathogenic fungi.

We go on to design models of microbial metabolism that identify species (B. longum, A. muciniphila) and metabolism pathways (histidine and arginine metabolism) which show strong differences betweem the two cohorts. The findings in this study can inform nutritional interventions and microbial metabolic pathways that play a role in fine-tuning our immune system. Read more in Nature Communications.