Charting responses to pathogens in human populations

The deal mostly works for both parties, most of the time. For the most part, microorganisms help boost our defenses, break down sugars, or produce useful small molecules, but oftentimes hitch a ride at our own expense. The resulting infections cause acute strains to our multicellular bodies, but may also cause severe long term consequences or death. To mitigate chances for undesired outcomes, innate and adaptive immune cells come to the rescue.

Sites of infection - Skin, guts, lungs or even bloodstream - may become conflict zones where the skirmish between innate immune cells and pathogens leaves behind piles of debris. These include proteins and peptides, their constituent parts. A diligent agent, and antigen-presenting cell, with its long arms is lurking in the background and fishing for foreign peptides. Some of this daily catch is presented to the T cells (thymus cells), elite decision makers, which are carefully selected to react against anything remotely different than our own peptides. Successful recognition of a foreign peptide causes a T cell to alert all sorts of immune system units, including calling in reinforcements (more innate immune cells), and crafting of antibodies, long-range weapons modelled after the freshly caught peptide. Their rapid multiplication also creates immune memory, ensuring faster responses in subsequent encounters with the same or similar villains.

Recognition of foreign peptides through antigen-presenting cells is one of the features of adaptive immune systems in complex organisms. In humans, the binding is carried out by major histocompatibility complex II (MHC-II), which are cell surface proteins and are extremely diverse across the population. It is an insurance policy, which uses a variety of fishing hooks and diversifies the portfolio of threats that would otherwise pass undetected.

Despite its importance, the diversity of MHC-II molecules and their targets has been understudied. In our recent work, we set out to investigate the recognition capacity of more than 40 uncharacterized variants of MHC-II molecules. Through engineering of antigen-presenting cells, Jihye Park produced cell lines that produce one type of MHC-II molecule each. Peptides bound to MHC-II molecules resulting from these experiments were then purified and identified by Jenn Abelin and her team, yielding 100,000s of resolved peptides.

Peptides are composed of amino acids, small molecules derived from DNA that are building blocks of proteins, which in turn govern biological processes. The alphabet of twenty amino acids forms a complex biological code, which not only determines functions of proteins, but can also serve as fingerprints to distinguish between our own and foreign peptides. A sequence of mere 10 amino acids can encode 10^20 = 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 different peptides. Peptides that elicit above mentioned immune responses are sometimes called epitopes, or immunogenic peptides.

Remembering rules in such a large universe is a big ask for our antigen-presenting and T cells.

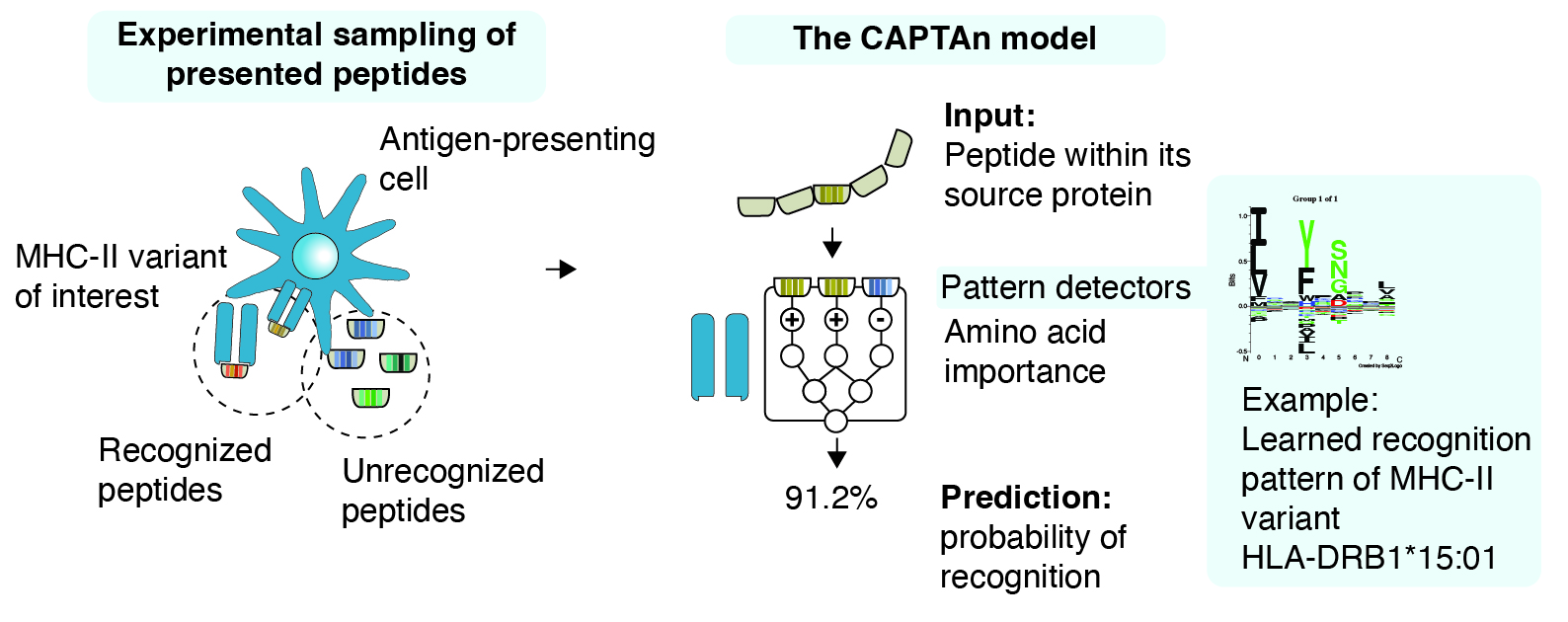

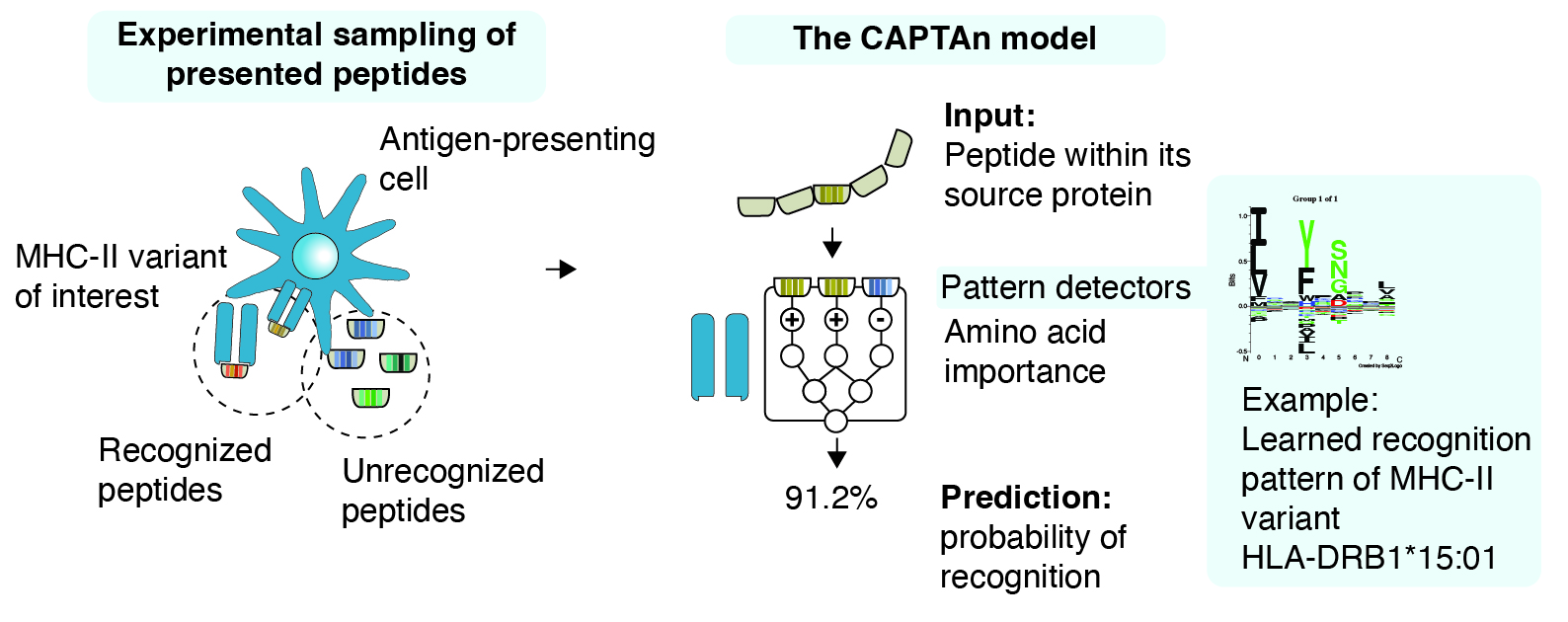

Statistical analysis of new data revealed many unexpected patterns in newly identified peptides and enabled inference of novel binding rules, especially for understudied families of MHC-II molecules (predominantly from the -DP and -DQ family). The dataset comes with a machine learning method we developed which seeks characteristic patterns of amino acids recognized by different varieties of the MHC-II molecules. Besides analyzing source sequence motifs, we implemented methods for analysis of whole proteins from which the potential immunogenic peptides are derived. This is important, since T cells like their peptides finely chopped in right places, which in turn depends on their accessibility and location within their source proteins. Some of the rules of how peptides are prepared, presented are therefore learned and provided by our model, termed Context-Aware Predictor of T-cell Antigens, CAPTAn.

CAPTAn allowed us to identify numerous novel immunogenic peptides, which improved our understanding of how our immune system recognizes commensal microbes and viruses. An experiment led by Thomas K. Pedersen identified immunogenic epitopes from commensal bacteria, which are thought to migrate from the oral cavity to the gut and potentially contribute to inflammation.

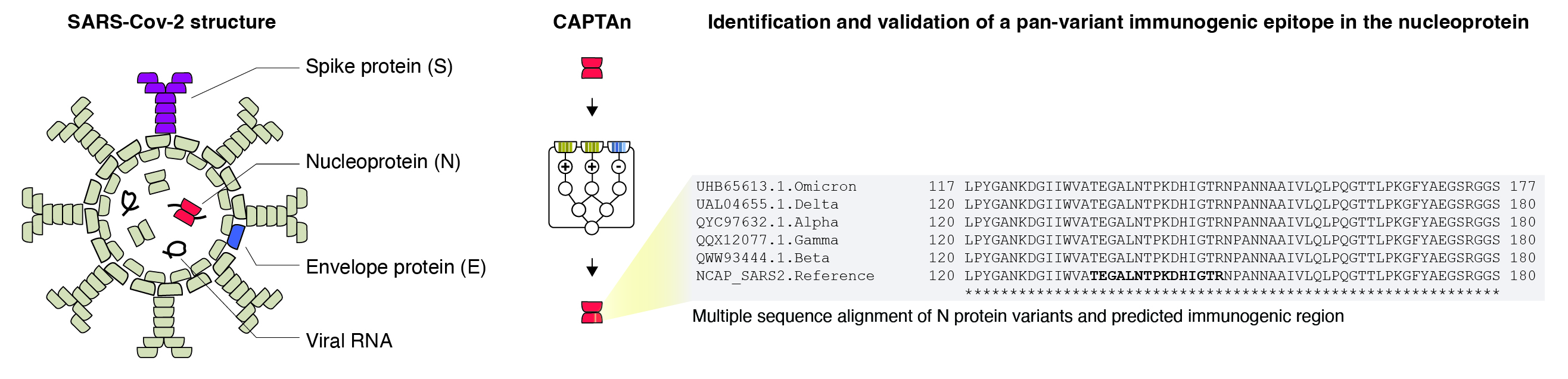

T cell responses may sometimes feel underappreciated relative to B cells and antibodies, which are premium responses to many severe infections. While T cell memory and responses may take longer time to develop, their advantage is that they can target more diverse pathogenic proteins. While antibodies are limited to target surface proteins, as in SARS-Cov-2 spike protein, T cell targets are essentially unrestricted. Therefore, while some pathogens can mutate their surface proteins more freely, they may have less wiggle room in structural proteins key to their survival.

Over the years, SARS-Cov-2 evolved into many variants-of-concern, which primarily differed in the efficiency of surface protein (Spike) attachment and entry into human cells. Using CAPTAn, we identified an immunogenic peptide within the nucleoprotein (N), a key protein in viral replication, which the variants appear to not mutate much, if at all. Targeting highly conserved regions may therefore provide lasting responses and yield promising peptide vaccine candidates. Peptide antigen presentation to T cells is thus an important part of adaptive immune responses, where collaborations between structural biologists and computational approaches lead the path forward. Continuous identification of novel immunogenic peptides will facilitate vaccine development, understanding of allergies and autoimmunity, and may even play a role in fighting cancer.

Read more in Immunity or try our CAPTAn software.