Eavesdropping on mouse and microbe stand-off in the gut

All animals provide room and board for bacteria, which are to large extent found in the intestines. Most bacteria are thought to be harmless and simply occupy space, and some provide health benefits, like tuning our immunity by making short chain fatty acids, or enzymes that help with digesting your oatmeal. Several bacterial species have also been associated with disease, which has to do with disruption of the mucosal barrier and chronic inflammation. We want to keep our friends close, but not too close.

Most contemporary methods to study microbiomes in humans rely on non-invasive sequencing microbial DNA in skin, saliva or stool samples. On the other hand, we profile the much larger animal cells by sequencing RNA, which says a lot about the current activity as well as the identity of host cells, all that on a single-cell level.

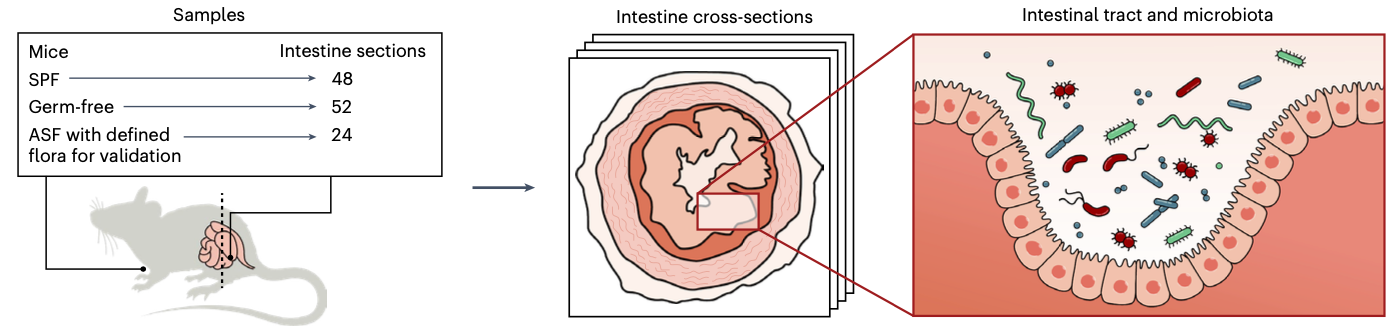

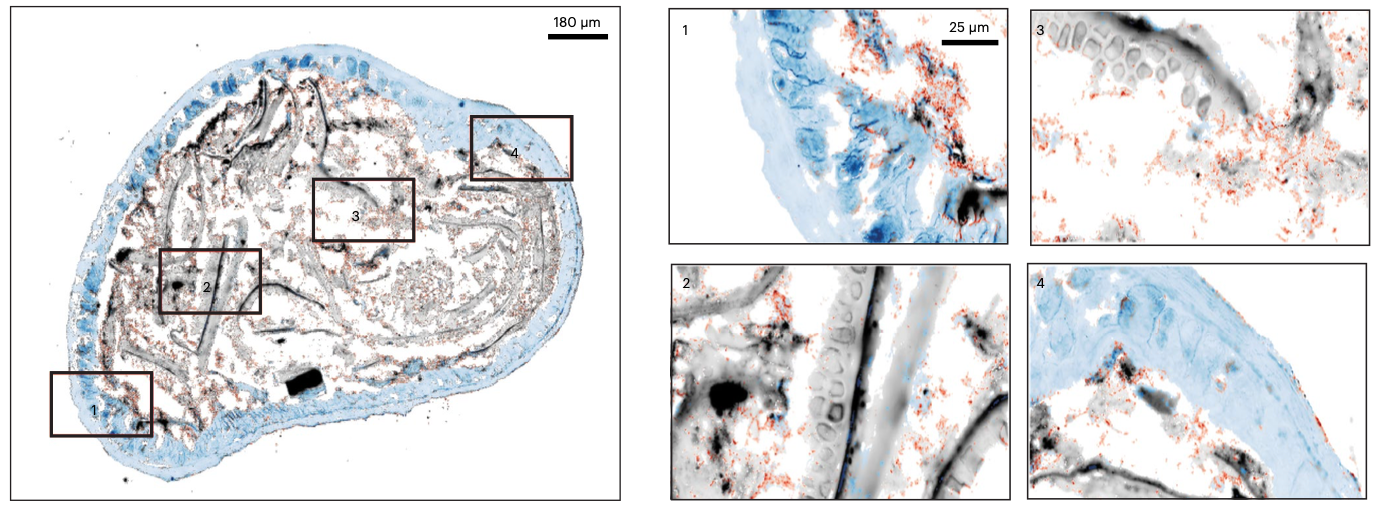

Spatial transcriptomics, billed as Method of the Year by Nature Biotechnology in 2020, have provided a lens towards profiling cell activity in tissue samples and linking RNA transcription to exact coordinates in space. Our recent study, led by Britta Lötstedt and supervised by Sanja Vičković, went a step further and developed both the SHM-seq technology and computational methods to profile joint host and microbial gene expression in the same tissue.

Britta and Sanja show how to slice the mouse gut and measure the activity of the host cells and identity of bacterial species in the same tissue section.

The article provides a recipe to scatter a glass slides with barcoded DNA probes, which fish for mature (polyadenylated) host RNA, and the bacterial regions of the 16S rRNA (which is among the most variable and allows for taxonomic identification on the genus level). The method comes with a custom machine learning approach, which is trained to map DNA reads to member of a pre-defined bacterial community. This last step enables maximizing the value of the data and leaves as few reads unassigned as possible.

This unprecedented resolution will enable researchers to study models of inflammatory diseases in the gut, and pinpoint the likely bacterial culprits. This is shown through comparison of sterile (germ free) mice versus colonized (SPF) mice, where we see pronounced changes in gene expression. Colonized mice tend to express genes for mucus production and thus seem to keep a distance between themselves and microbes. Conversely, sterile mice seem to enjoy a tranquil moment of solitude and activate genes for epithelial repair. Some bacteria can get closer to the gut lining than others, which makes them interesting in studies of host-microbiome interactions.

In the near future, spatial host and microbiome sequencing technologies are poised to visualize and quantify the interplay between microbes and their host directly at the crime scene.

Learn more in open access at Nature Biotechnology.